The Blue Jays went from 19th in baseball with a .241 batting average in 2024 to 1st in baseball with a .265 average in 2025. With their turnaround from worst in the division to a World Series appearance the following year, I thought now was the perfect time to dive into a question I was asked recently: “Why don’t we see many players in today’s game with a batting average over .300?”

It’s a great question, and one that doesn’t have a simple answer.

My initial hypothesis was that a few major factors were at play: defensive shifting, pitchers throwing harder with better stuff, and the overall advancement of pitcher preparation and game planning. To test that, I dug into some data to see whether those assumptions held up, especially given the ongoing debate between baseball generations about the current state of offense.

Setting the Stage

Here’s a quick reference from one of my previous blogs, Revolutionizing Offensive Metrics: Exploring wOBA, Fastball Success, and the Keys to Scoring Runs in 2024.

- Batting Average (AVG) has a correlation of 0.804 and an R² of 0.691 with runs per game. → About 69% of the variation in runs per game can be explained by batting average alone.

- On-Base Percentage (OBP) has an R² of 0.865, showing it’s even more predictive of run scoring.

- wOBA has an R² of 0.924, and OPS nearly matches it at 0.919, both far stronger predictors of run production than batting average.

I share this not to downplay batting average, it’s still valuable, but to show that other metrics provide a clearer picture of offensive success. Still, this post focuses solely on batting average: why it’s declined, and what’s really driving that trend. And because averages are still a part of the other stats that today’s game likes to use.

Research and Historical Trends

All data below comes from FanGraphs. I started in 1961, the year MLB expanded from 16 to 18 teams (and also the year my hometown Twins came into existence).

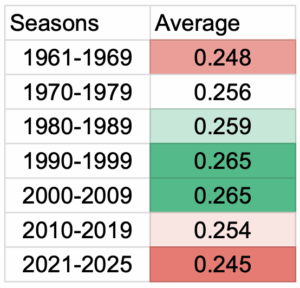

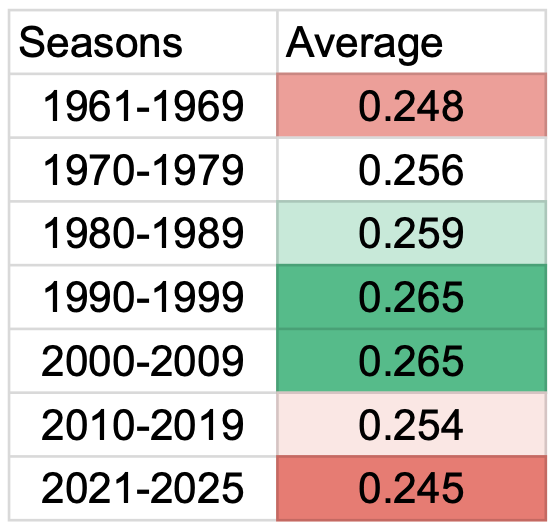

Average Batting Average by Decade:

Let’s add some context to those numbers:

- 1960s: MLB expanded, diluting talent slightly for a few years. The “Year of the Pitcher” (1968, Bob Gibson’s 1.12 ERA) led to the mound being lowered from 15” to 10” in 1969.

- 1970s: Slight uptick in averages; the introduction of Astroturf in some parks sped up ground balls.

- 1990s: The steroid era began and the league expanded again (to 30 teams). Averages peaked at .265.

- 2010s: The shift era—defensive positioning began to take away ground-ball singles. Pitchers also started adjusting usage patterns.

2020s: Velocity is higher than ever, the shift has been banned, and hitters are facing the best “stuff” in history. (Yes, velocity is much higher now than ever before. Pitchers throw significantly harder today on average than they did even 10 years ago when I played.)

BABIP: Batting Average on Balls in Play

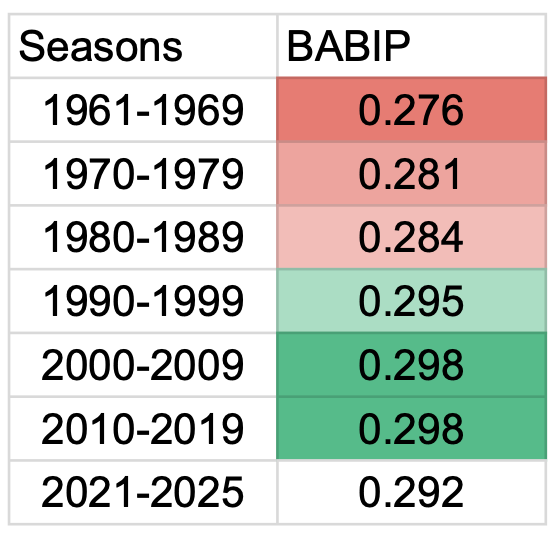

To better understand these averages, let’s isolate the effect of contact, let’s look at BABIP over the same time frame. Essentially we’re taking out strikeouts and only looking at the outcome of all balls put in play:

BABIP was much lower in the 60s and 70s, climbed steadily through the 80s, and then jumped in the 90s, likely a combination of higher exit velocities, improved bats, juiced balls (and maybe some players), and a short-term dilution of pitching talent due to expansion. It has remained fairly steady since the 1990’s however.

As we know, balls hit 95+ mph are far more likely to become hits. The quality of the bats and balls of modern eras likely played a role here too; lighter, more balanced bats compared to the ‘tree trunks’ swung by hitters decades ago. (Which makes their skills even more impressive in my opinion).

Interestingly, BABIP hasn’t fluctuated as dramatically as batting average itself. That suggests that balls in play haven’t changed outcomes as much as we think, meaning defensive shifts weren’t as responsible for the drop in averages as I believed. (So much for my shifting theory.)

That brings us to the other side of the equation: pitching.

Pitching Trends

For this section, I used data from 2002 through 2025, since more advanced pitch metrics weren’t as available before then. I believe the differences we will find in just these 24 years give us tremendous insight into trends throughout the broader baseball history.

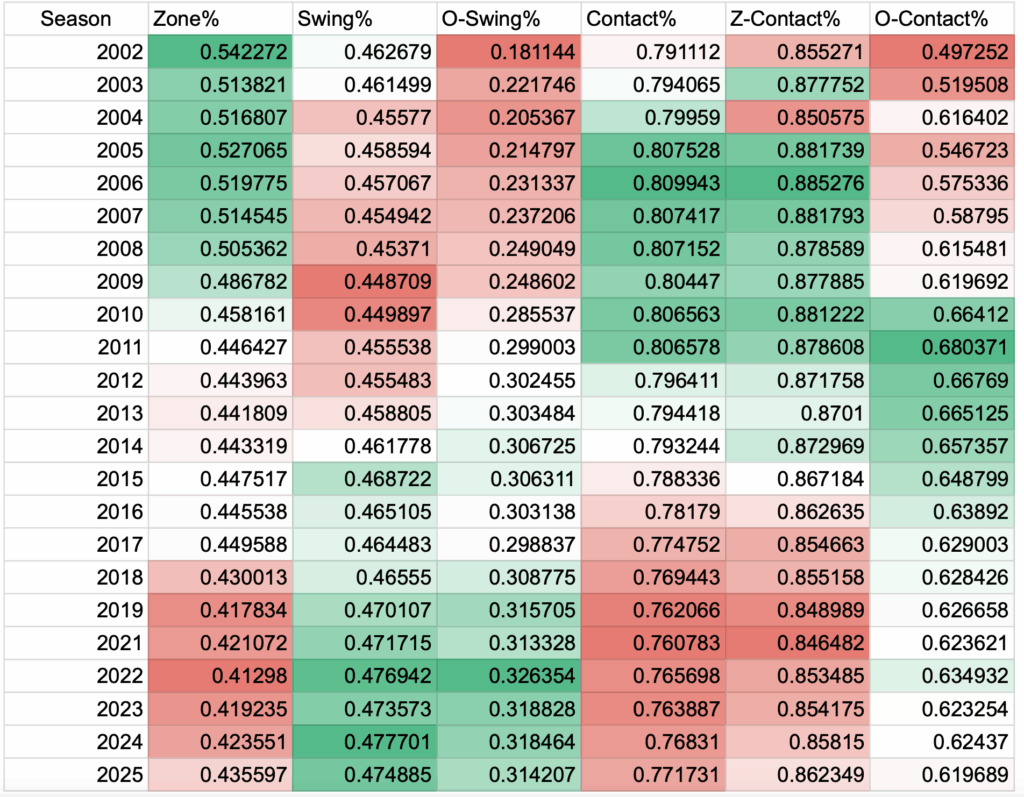

Let’s start with zone percentage, the percentage of pitches thrown inside the strike zone. Over the past two decades, In-zone percentage has dropped by roughly 10%. These are simply just pitches in the strike zone, not whether or not the batter swung.

Meanwhile, swing rates have stayed mostly consistent (around 45-47%), but out-of-zone swing rates have increased, meaning hitters are expanding outside the zone more often because pitchers are throwing fewer strikes.

Contact rate has also dipped by about 3-4%, both overall and on pitches in the zone. The one area where contact has increased is on pitches out of the zone, which does also make sense given the rise in these chase swings.

So, the question is why are hitters seeing fewer strikes and making less contact overall?

The answer lies in pitch usage.

Fastballs vs. Everything Else

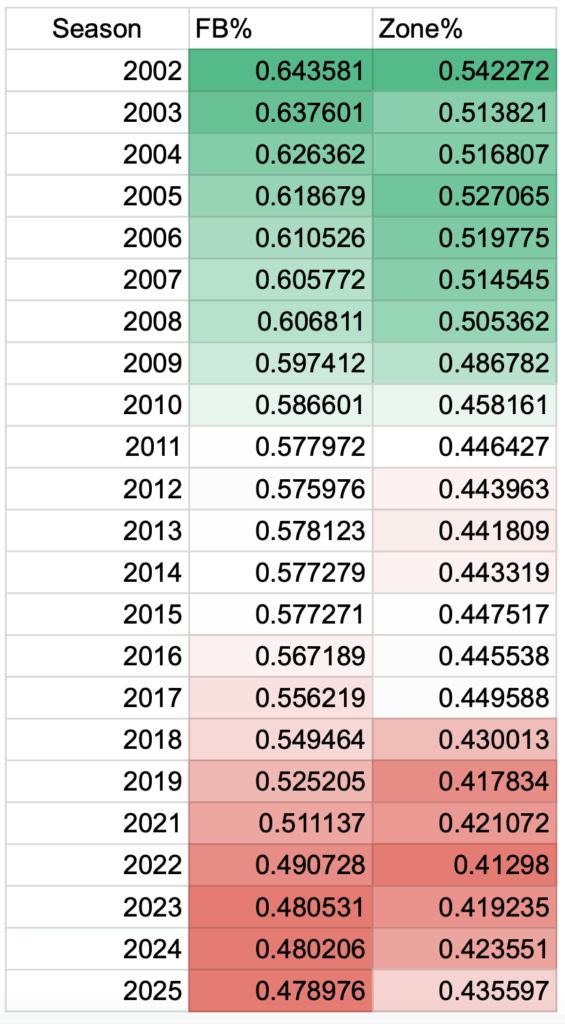

Pitchers are throwing fewer fastballs than ever, and those are the pitches most likely to be in the zone.

2025 Zone% by Pitch Type:

- Fastballs: 57.2%

- Breaking Balls: 45.9%

- Changeups/Splitters: 39.3%

When fastball usage goes down, the total number of strikes in the zone naturally drops. Pitchers are living on breaking balls and changeups, pitches that look like strikes early and finish off the plate.

In other words: today’s pitchers aren’t just throwing harder (which I won’t get into), they’re throwing smarter.

The result?

- Fewer pitches in the zone.

- More swings at non-strikes.

- Less contact overall.

And that combination has a direct relationship with strikeouts. In 2025 alone:

- In-zone miss rate had an R² of 0.742 with strikeout rate.

- Overall miss rate had an R² of 0.867 with strikeout rate.

The takeaway is probably very obvious: the more hitters miss, the more they strike out, and pitchers are better than ever at creating those misses.

Conclusion

When we look at contact ability through the lens of pitch usage, it’s clear that today’s offensive environment is driven heavily by how pitchers attack, not necessarily by hitters getting worse.

Pitchers are better at mixing pitches and designing sequences that exploit swing decisions. They’ve likely evolved faster than hitters have been able to adapt.

So, circling back to my original hypothesis:

- I was partly right: pitchers are better and more advanced.

- I was wrong about shifting being the main reason.

The data tells us that hitting in today’s game is likely harder than ever, but for different reasons than many assume. It may not be the hitters’ approaches and inability to make contact. The strikeout increases are heavily due to pitchers adjustments in sequencing and deception.

So I’ll leave you with one question to ponder:

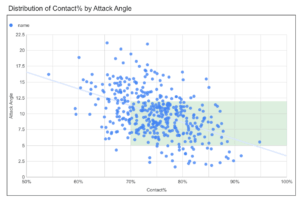

Can you actually improve contact rates?

P.S. No hitter in the history of baseball has ever liked striking out – or been “okay” with it. I can promise you that.